![]()

A Franco-Flemish double-manual harpsichord,

![]()

Details of the modern history of this instrument

The modern history of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord

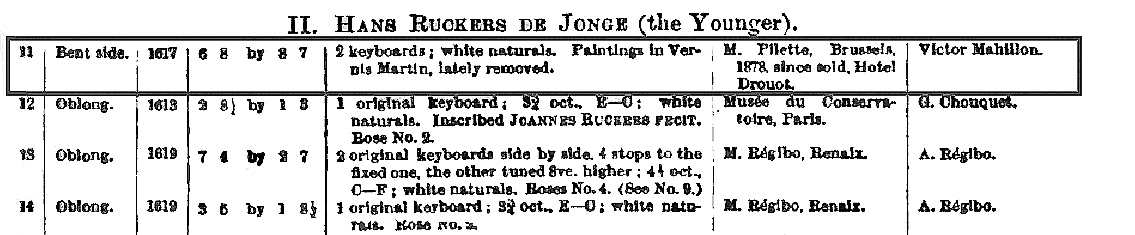

The oldest known record of this harpsichord in the modern period comes from the first edition of The Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Ed. George Grove (Macmillan Pub., London, 1883) p. 197 which lists the instruments then thought to be by the various members of the Ruckers family:

The entry outlined above with a heavy line refers to this instrument which is also referred to in subsequent editions of The Dictionary of Music and Musicians as having once belonged to M. Pilette of Brussels. The publication of this entry [1883] follows shortly after the date 1878 when the instrument was known to have belonged to 'M. Pilette' in Brussels. The source of the information is Victor Mahillon, Curator of the Brussels Museum of Musical Instruments, and so is probably reliable. However, the statement: ‘Paintings in Vernis Martin, lately removed’ in the above entry must refer, not to the external decorations which clearly still exist even to this day, but to the soundboard decoration which, along with the date, was removed in this early period. This is confirmed by the later editions of Grove's Dictionary which do not give the date but list the instrument as ‘n.d.’ = no date The soundboard was later decorated (without a date) possibly by Mabel Dolmetsch (1874 - 1963) when it belonged to Arnold Dolmetsch (1858 - 1940). The subsequent entries in the later editions of Grove's Dictionary make it clear that this entry does in fact refer the same instrument.

In the later 4th and 5th editions of Groves Dictionary referred to in the first edition of Boalch's list (below) of instruments[1], slightly more information is given. A scan of the entry from Boalch is given below:

This indicates that it was bought by Arnold Dolmetsch at auction from the Hôtel Drouôt in Paris, although there is no indication here of when this happened. Dolmetsch then sold it on to Mrs. H.E. Crawley, wife of a Second Lieutenant and Honorary Captain in the British Army (1902)[1]. Mrs. Crawley (neé Violet Gathorne-Hardy (1873-1952) was well-known as an amateur harpsichordist and was tangentially involved with the so-called 'Bloomsbury Group'. She and her husband were also personal friends of Arnold Dolmetsch and they were members of the Dolmetsch inner circle. Around 1902, at the time of her marriage, this included such figures as William Morris, Selwyn Image, Roger Fry, Gabriele d’Annunzio, George Bernard Shaw and Ezra Pound.

The statement that the harpsichord was sold to William Randolph Hearst in 1951 is incorrect. In fact it was sold in a Sotheby's London sale on 13 May, 1927, and it was presumably at this time that it was bought by William Randolph Hearst during one of his forays to Europe to buy fine art and fine furnishings for his Castle, San Simeon, in California (see the discussion below). It is known that the instrument was already in South America in 1941.

Click on this image to see details of the Sotheby's sale catalogue. (See also the image below.)

![]()

This is the same instrument as that listed in my book Ruckers. A Harpsichord and Virginal Building Tradition, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990) on page 277. The entry in my book (which I wrote before ever seeing the instrument!) reads as follows:

“ ‘n.d.d HR’

‘Hans Ruckers’, undated, double-manual harpsichord formerly the property of the Hearst family, New York, present location unknown, B. 28 = 32.

A large double-manual instrument. Photographs of this instrument in the Russell Collection Edinburgh, show it to be a beautifully-decorated harpsichord, probably of French origin. It has a compass of F1 to f3, painted decorations in the style of Boucher, and a gilt stand in the style of Louis XV. The width of the tail is too great for it to have been a Ruckers instrument.”

Mentioned in this entry is a black and white photograph which is in the Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments in Edinburgh (where the author was once the Curator/Director. This photograph and its reverse side is shown below.

The front and rear of the photograph of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord in the Russell Collection, Edinburgh. The date of the photograph is 1927.

This is clearly the same instrument as that under study here. It has the same stand, lid decoration, case decoration and keywell decoration as the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. The inscriptions on the back of the photograph are intriguing. The top left-hand inscription seems to be the number of the negative from the photographic studio that originally printed the photograph. To the right of this is ‘HR ex WR Hurst’ written in ball-point pen in the hand of Raymond Russell. This seems to indicate that this photograph once belonged to Russell and that it was part of his own large archive of photographs of early keyboard instruments. This part of the inscription, at least, may therefore date to a period in the 1950’s when Russell was actively collecting instruments, photographs and information for his book[2] and when he was also writing the ‘Ruckers’ entry for the 1954 edition of Grove’s Dictionary. The spelling of ‘Hurst’ has been corrected to ‘Hearst’ in pencil and this, and the subsequent inscriptions also in pencil, are all in the hand of Prof. Sydney Newman who was a member of the Faculty of Music at the University of Edinburgh and who was instrumental in the foundation of the Russell Collection of Early Keyboard instruments there. Prof. Newman annotated many of Russell’s notes, photographs and books that came to the Russell Collection from Russell’s estate when the Collection was bequeathed to the University.

The date of this photograph is not known. However, it is likely that it was taken during the early period when it was in England (about 1920-1925) or it was taken slightly later when it arrived in San Simeon Castle built by Hearst in California (see the section below). Whenever the photograph was taken it is clear that it had the present nineteenth-century stand and that there were no knee pommels for a genouillère. It also still had the fake 'IOANNES RUCKERS ME FECIT ANTVERPIÆ' namebatten, a strange set of register levers, and that the nameboard was not removable. It had therefore clearly lost the genouillère by the time the photograph was taken.

The Tomasini connection

A harpsichord by Louis Tomasini, made for the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, survives in the Berlin Musikinstrumentenmuseum in Berlin:

Click here to see an image of the double-manual harpsichord

by Louis Tomasini, 1899, in the Berlin Musikinstrumentenmuseum

Not mentioned in any of the references above is any connection with Louis Tomasini (April 11, 1845 - August 31, 1899). However, additions to the decoration on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord are clearly in the same hand as that of the decorator of the Tomasini double-manual harpsichord in the Musikinstrumentenmuseum in Berlin (above).

Comparison of the Tomasini decorations

The comparison of the decoration in these photographs make it clear that the Franco-Flemish harpsichord must have been restored and the decoration 'improved' by Louis Tomasini in about 1889 (the time of the Exposition Universelle in Paris for which the Eiffel Tower was built). Tomasini built and exhibited one of his own instruments at the Exposition Universelle, and the comparison above indicate that he used the same decorator as he used for his own instruments to add 'extra' decorations to the Franco-Flemish instrument.

One of the unusual features of the Tomasini harpsichord seen in the link above is that the bridges are painted in gold paint or bronze powder. The Franco-Flemish harpsichord also has this unusual feature. It therefore seems likely that Tomasini had the bridges of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord painted gold as well as adding the 'extra' decorations to the jackrail, nameboard and the outer lid battens indicated above.

Click here to see a larger image showing the gold-painted bridges of the Tomasini double-manual harpsichord

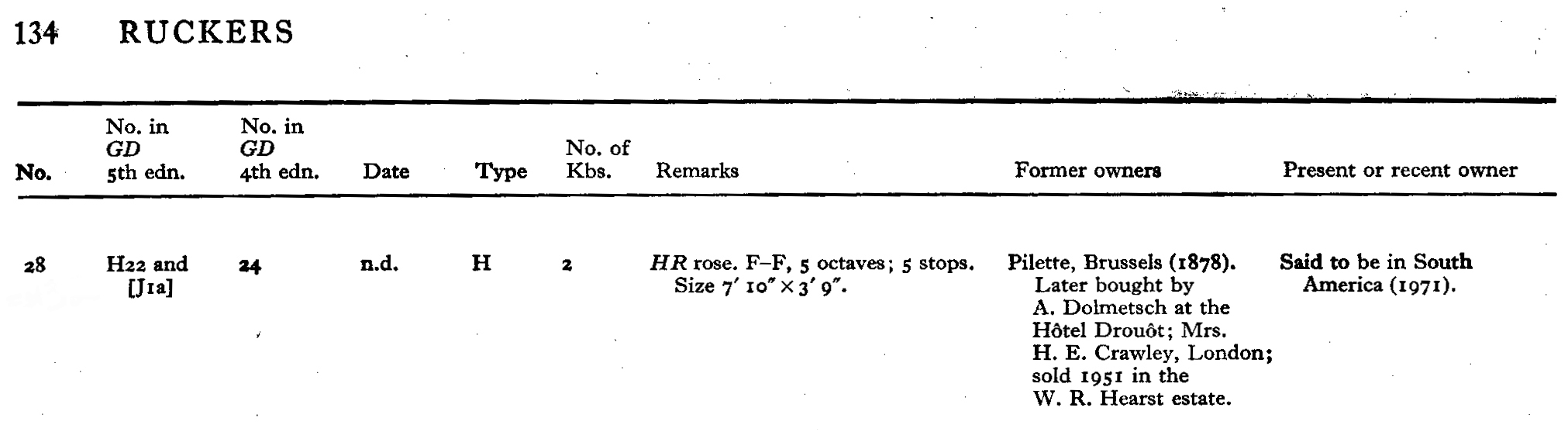

The route to Tomasini's interest in the harpsichord is fascinating and very informative regarding the early modern harpsichord revival interest in the harpsichord. Emile-Alexandre Taskin (1853-1897), who was a baritone with the Opéra Comique in Paris, became fascinated with the world of the, by then, long forgotten harpsichord. It seems likely that this fascination arose because one of his forefathers was a renowned keyboard builder - none other than Pascal Taskin the court harpsichord builder to Louis XV and Louis XVI. Adolphe-Gustave Chouquet, then curator of the musical instrument collection of the Paris Conservatoire, was approached by Emile-Alexandre Taskin about the possibility of buying an instrument made by Emile-Alexandre's forefather. By chance Chouquet had come across an instrument in a second-hand shop in provincial France during his search for old instruments and, also by chance, this harpsichord was indeed by Taskin’s forefather. The instrument was none other than the 1769 Pascal Taskin double-manual harpsichord now in the Russell Collection at the University of Edinburgh, and one of the most famous and certainly the most copied harpsichord in the world!

Emile-Alexandre Taskin (Paris, 18 March 1853 - Paris, 5 October 1897)

Emile Alexandre Taskin loaned his 1769 Taskin harpsichord for concerts given by Louis Diémer for a period spanning about 30 years following its initial restoration by Tomasini in 1882. This time included the time of the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889 Emile-Alexandre Taskin loaned his harpsichord to Louis Diémer for a series of concerts given during the period of the Exposition. These concerts were so successful that it eventually led to the foundation by Henri Cassadesu in 1901 of the Société des Instruments Anciens, an organisation which lasted almost 50 years and dedicated itself during this period completely and successfully to the performance of early music in Paris.

The restoration of the 1769 Taskin harpsichord bought by Emile-Alexandre Taskin was entrusted to Louis Tomasini. A branded stamp on the wrestplank of the 1769 Russell Collection Taskin harpsichord bears the inscription: “REFAIT PAR LOUIS TOMASINI EN 1882” recording the date of the restoration. This is probably therefore the earliest example of historical keyboard restoration in modern times!

Tomasini's newly-restored instrument, the famous 1769 double-manual Taskin harpsichord, and 'The golden harpsichord' - presumably the Franco-Flemish harpsichord - were played by Louis Diémer (b. 1843 - d. 1919), one of the most important figures in the revival of interest in the harpsichord and harpsichord music. In the period around 1889 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris there was an amazing revival of interest in early music and in its performance. In parallel with this there was a sudden flourish among instrument makers in the production of early keyboard instruments. The piano and harp manufacturer Érard, for example, produced 3 harpsichords for the Exposition Universelle (one of which at least also survives in the Berlin Musikinstrumentenmuseum). But, as mentioned above, the keyboard-instrument maker Tomasini, and the piano firm of Pleyel, Wolff, Lyon & Cie also exhibited instruments in the Universal Exhibition.

As has already been made clear above from the similarity of their decorations, Tomasini's decorator must have added to the decorations on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord around the time of the Exposition Universelle in 1889. It seems highly likely that Le clavecin doré played by Diémer his series of concerts is just the Franco-Flemish harpsichord, and that it must also have been among those played by Diémer in the Exposition Universelle concerts in Paris. The stunning gilt and painted decoration and the exuberant gilded stand would have made this harpsichord an immediate choice for Tomasini to exhibit, and for Diémer to play during the Exposition Universelle. It therefore would seem to be almost a certainty that an instrument which was so 'French', with its vernis martin gold decorations and the outer lid paintings by François Boucher would have been chosen for this celebration of everything interesting, beautiful and French. It would almost certainly have been among the antique and modern harpsichord exhibited and played then.

One of the unusual features of many of the historical instruments restored by Tomasini with the normal disposition of 2x8', 1x4' is that he changed the plectra of the main lower-manual row of 8' jacks from bird quill to peau de buffle. It's true that the sound of the peau de buffle register is beautiful and ethereal, but historically it is used as an extra fourth register in an instrument which already has 3 registers with quill plectra giving a 2x8' and 1x4' disposition. The role of the peau de buffle is really when it is used with the other principal registers and with the genouillère to produce the expressive effects and contrast of the full classic plien jeu reduced gradually to the quiet sonority of the peau de buffle. To replace the quill of the lower-manual 8' with a peau de buffle register means that Tomasini did not understand the role that the peau de buffle played in conjunction with the genouillère in historical instruments with a genuine peau de buffle. To replace the main voice of a harpsichord with the sound of a peau de buffle register clearly means that Tomasini saw the role of the peau de buffle as an individual solo stop. As such it would be ineffective when used with the upper-manual 8' register, or as part of the plien jeu.

So where did Tomasini get the sound and idea of changing the rear, lower-manual quill register to a peau de buffle register from? The list of Tomasini's known restorations of historical instruments does not, to my knowledge, include any which originally had a genouillère or a peau de buffle register - except for this Franco-Flemish harpsichord. It is not in the list of Tomasini restorations because it has only just been discovered recently by me to have been restored by Tomasini. I now feel fairly certain that the idea of the peau de buffle register actually came to Tomasini from this Franco-Flemish harpsichord which was equipped with this feature. I know of no other harpsichord restored by Tomasini that originally had a peau de buffle register. This therefore makes the Franco-Flemish harpsichord the original source for Tomasini's interest in and use of the peau de buffle register in his 'restorations' of other historical harpsichords. In some ways, therefore Emile-Alexandre Taskin, great grandson of the famous harpsichord builder Pascal Taskin, can be seen as the ultimate inspiration for the modern harpsichord revival!! Tomasini, as the restorer of the 1769 Taskin harpsichord in 1882 and of this Franco-Flemish harpsichord around the time of the Exposition Universelle also takes his place in the Hall of Fame as the first person in modern times to restore an antique harpsichord. He is also among the first to build a copy of an original antique harpsichord that is accurate at least in its overall appearance! The Franco-Flemish harpsichord is also therefore one of the first harpsichords to be restored during the modern era.

The Dolmetsch connection

As noted above the Franco-Flemish harpsichord was apparently bought by Arnold Dolmetsch at the Hôtel Drouôt in Paris, although the date of the purchase is not mentioned in the Dolmetsch archives. Dolmetsch, after leaving his father's piano workshops in Le Mans, France, went to Brussels where he studied music at The Brussels Conservatoire. He studied the violin with at first with Henri Vieuxtemps and then in 1883 he traveled to London to attend the Royal College of Music, where he studied under Henry Holmes and Frederick Bridge. He was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree in 1889, the year of the Exposition Universelle in Paris. He then remained in London until he left England to build clavichords and harpsichords for the firm of Chickering of Boston (1905–1911), and then for Gaveau of Paris (1911–1914). Hence he was not in Paris until the period 1911 to 1914, and it seems likely therefore that it was in this period that he would have bought the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. He must then have taken the instrument to London in 1914 where he began working as a professional harpsichord and clavichord maker and restorer.

As has already been mentioned, Dolmetsch was trained in his father's piano factory in France, and much of his harpsichord-building style reflects the piano tradition rather than the historical harpsichord tradition (my mentor John Barnes very aptly referred to the type of instrument that Dolmetsch and his contemporaries built at this time as 'pianochords' since they were really constructed structurally, acoustically and mechanically like a piano, except that they had a plucking mechanism). Unfortunately the piano tradition also affected Dolmetsch's restorations of antique instruments as well. For example, he removed the original Taskin genouillère from the 1764/1784 Goermans/Taskin harpsichord, now in the Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments at the University of Edinburgh, and replaced it with a pedal mechanism of his invention 'because the instrument was too fragile' to withstand the use of the genouillère mechanism! Dolmetsch also added a number of soundbars (John Barnes called these 'stifle bars') underneath the bridges of this instrument, thus stiffening the soundboard considerably and greatly stifling the sound of the instrument. Dolmetsch's third wife, Mabel Dolmetsch (1874-1963) removed and 'restored' a number of the flower groups on the soundboard and wrestplank of both the 1764/1784 Goermans/Taskin harpsichord and, possibly, of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. The soundboards of both of these two instruments were coated with a thick, uneven layer of oily varnish. When the Goermans instrument was restored by me in the 1970's this varnish looked more like a layer of brown gravy than varnish. A number of Dolmetsch's other restorations also exhibit many of these same features.

Needless to say, Dolmetsch couldn't leave the Franco-Flemish harpsichord alone either. He added numerous 'stiflebars' underneath both bridges below the soundboard, and the soundboard was also coated in a thick layer of oily brown varnish. The painting of the soundboard flower groups and the borders and arabesques are in the style of Mabel Dolmetsch who painted or re-painted many of the other instrument either made or restored by Arnold Dolmetsch. It is therefore likely that the author of the soundboard painting on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord is Mabel Dolmetsch, although there now seems to be no surviving evidence to confirm this.

Click here to see photographs comparing the case decoration before and after the removal of the linseed-oil varnish.

The William Randolph Hearst connection

William Randolph Hearst was born in San Francisco on 29 April, 1863, the son of a gold mine owner and US Senator, George Hearst. After receiving a good education the younger Hearst took control of the struggling San Francisco Examiner, a newspaper which the elder Hearst had bought in 1880. William Randolph remade the Examiner, and later a number of New York papers, into a blend of reformist investigative journalism and lurid sensationalism. By 1925 Hearst had established or acquired newspapers in every section of the United States. These newspapers soon attained an unprecedented circulation and earned Hearst an immense fortune. In the 1920s he built a grandiose castle on a 240,000-acre ranch at San Simeon, California, and he furnished this residential complex with a vast collection of antiques and art objects that he had bought in Europe.

At the peak of his fortune in 1935 he owned 28 major newspapers and 18 magazines, along with several radio stations, movie companies, and news services. But his vast personal extravagances and the Great Depression of the 1930’s soon seriously weakened his financial position and he had to sell some of his faltering newspapers or bad enterprises. In 1937 he was forced to begin selling off some of his art collection, and by 1940 he had lost personal control of the vast communications empire that he had built up. He lived the last years of his life in virtual seclusion and died on August 14, 1951.

It therefore appears that Hearst must have bought the harpsichord, probably in the 13 May, 1927 Sotheby's sale, from Mrs H.E. Crawley who, incidentally, also once owned the 1764/83 Taskin/Goermans in the Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments. Although Boalch says that the Franco-Flemish harpsichord was sold in 1951 (presumably assuming that it was sold after the death of Hearst in 1951) it is known that the instrument was already in Argentina in the mid 1940’s and so must have been among the items that were sold in the period shortly after 1937 when Hearst was on the verge of bankruptcy. It is not clear who then bought the instrument from Hearst nor how it found its way to Argentina.

The history in South America and the 'restoration' by Roberto de Regina in São Paulo in Brazil

Most of the information in this section originated by word of mouth from the former owners of the instrument communicated to me personally. The harpsichord was first seen by the former owners in the mid 1940’s in Buenos Aires in the window of an antique shop run by an Austrian antique dealer who, it was said, later dealt in Nazi war loot and the property of aristocratic Argentines. The owner then next saw the instrument at a house-warming party of Mrs. Gambarotta in Bariloche in Southern Argentina (Southern Andes). The Gambarottas supplied the mattresses for a new hotel Mrs. Gambarotta was running in Bariloche. The former owner’s father supplied the waste material for the Gambarotta’s mattress factory. The harpsichord had been given to Mrs. Gambarotta by General Pistarini[3] during the Peron era[4]. According to the former owners, General Pistarini had been given the harpsichord by Juan Peron in recognition of Pistarini's services to Peron in serving the Argentinean Government during the time of Peron's presidency.

After Mrs. Gambarotta’s husband died she fell onto hard times, and then she also died not long after her husband's death. What remained of her estate including the harpsichord was sold to pay off her debts. The former owners’ next encounter with the harpsichord was in the early '50’s. They saw it in the shop of a French antique dealer in Buenos Aires who asked at great deal of money for it. However, the dealer eventually wanted to return to Europe and contacted the former owners before leaving. The dealer asked if the former owners were still interested in the purchase of the instrument. They replied that they were, but that the price was too high. The dealer suggested that the former owner offer an acceptable price and the sale was agreed at the price offered.

When the harpsichord was first bought by the former owners from the antique dealer in Buenos Aires, it was unplayable. So the owners decided to have it restored. Some time after they had moved to São Paulo in Brazil in 1967, the owners met Roberto de Regina who had been an apprentice with Frank Hubbard in Waltham, Massachusetts. De Regina agreed to restore the instrument and took about 8 months to complete the work. De Regina replaced the baseboard (and with it the unique internal genouillère mechanism and also the calling card of Jacques Barberini which had been glued to the baseboard). He also replaced the 1786 wrestplank and nuts and changed the string scalings and plucking points in the process. He worked on the action and jacks, re-strung it and re-voiced it. It seems highly probable that he also lost the namebatten since it is clearly visible in the photograph shown above taken before the harpsichord went to South America.

Eventually these owners decided to sell the instrument and it was sent to me to examine, measure, analyse and, eventually, to restore.

Since then it has been the object of intensive investigation and study. During this period it has been kept in a humidified room in darkened conditions. The investigations and the restoration have continued here in Edinburgh. This report, among others, has been the result of these investigations.

![]()

Some of the former owners of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Arnold Dolmetsch (1858 - 1940) |

Mrs. Eliza Inez Crawley, wife of G.B.Crawley and mother of H.E. Crawley (1841 - 1913) |

William Randolph Hearst (April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) |

General Juan Perón, President of Argentina (1895 - 1974) |

General Juan Pistarini Argentinean Military General (1882 - 1956) |

[1] This is a short-hand reference to entries 28 and 32 listed under ‘Ruckers’ in the second edition of Donald H. Boalch, Makers of the Harpsichord and Clavichord, 1440-1840, (George Ronald, London, 1956; 2/Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1974) p. 134.

[2] Raymond Russell, The Harpsichord and Clavichord, (Faber and Faber, London, 1959; 2/Faber and Faber, London, 1973, revised by Howard Schott).

[3] General Juan Pistarini (1882 – 1956) was at first Minister of Public Works (1942 – 1952) and then Vice President of the Republic of Argentina during Juan Peron's presidency (see footnote 4 below). The Buenos Aires Public Airport is named after him.

[4] General Juan Domingo Perón was President of the Republic of Argentina from 1946 – 1955 and again from 1973 until his death in 1974.

![]()

Important

Features of this harpsichord

![]()

A brief history of the musical and decorative states of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord

![]()

Details of

the original state of the instrument

![]()

Details of the eighteenth-century states of this harpsichord

![]()

A problem encountered in the ethical restoration of this harpsichord

![]()

![]()

Go back to the main page of this section

![]()

This page was last revised on 24 January 2018.