Characteristics of the Neapolitan School of Harpsichord Building

The harpsichords built in the Neapolitan tradition have a number of features and characteristics that distinguish them from instruments made in other parts of the Italian peninsula. But, as with so many products of human endeavour, there are examples that break the rules and there are therefore some exceptions to those characteristics listed below. However, I will list some of the most common features of a large number of the examples that I have seen and studied in order to help the interested observer. These are listed below.

1. The lower mouldings and the case sides project below the level of the lower surface of the baseboard. This can be seen below in photographs taken of several different Neapolitan harpsichords.

![]()

2. The outer edges of the cap moulding do not project beyond the edges of the mouldings on the inside and outside of the top of the case walls but are flush with them on both sides (see the drawing in item 4 below). Normally, in instruments made north of Naples, the edges of the cap moulding project well beyond the mouldings below it and indeed the inside top case moulding is often lacking and not part o the normal construction procedure at all.

![]()

3. The lower outside moulding that surrounds the whole of the case sides is relatively high and relatively thick (see the drawing in item 4 below).

![]()

4. There is a strip of hard wood (often of sweet chestnut) hidden below the lower outside case moulding. This strip is not as high as the lower outer case moulding. Often the various pieces of this strip of wood are joined at the corners of the instrument with simple overlapping joints rather than the careful mitre joints of the lower outer moulding and of the main case sides higher up. This strip is shown with shading at the bottom of the drawing below.

Schematic drawing of a section of the case sides

Harpsichord attributed by me to Onofrio Guarracino, c. 1690, Naples

Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Catalogue Nš 1933.0543

![]()

5. Very often (but not always) the angle of the tail of the harpsichord is very acute. The harpsichords by Onofrio Guarracino exhibit this feature (see the drawing below) but the anonymous Neapolitan harpsichord in the Russell Collection (seen in plan view below) is one of several exceptions to this rule.

Drawing of the baseboard of the harpsichord by Onofrio Guarracino, 1651, Andrea Coen, Rome, showing the tail angle of only 30°.

Anonymous harpsichord, Naples, c.1620, with a large tail angle of 57.7°

I have not given the website address here as the University is constantly changing it! Good luck finding it yourself!!!

Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments, University of Edinburgh

![]()

6. The case sides are normally of cypress, but occasionally they may be of maple or sycamore. The use of the latter materials seems to be unknown outside of Naples, but the use of cypress does not preclude the instrument being Neapolitan as, indeed, most Neapolitan harpsichords have case sides of cypress.

7. The jackrail support system is very characteristic of the Neapolitan school of harpsichord building. In this system a small notched bar is attached to the inside of the case above the registers and a correspondingly notched slot in the end of the jackrail slides over this bar. Most harpsichords built north of Naples have the opposite system: there is a forked piece of wood glued to the inside of the case and a tenoned projection on the end of the jackrail slides into this. A typical Neapolitan jackrail support can be seen in the photograph below.

The jackrail support and the bass end of the jackrail

Harpsichord attributed by me to Onofrio Guarracino, c. 1660, Naples

Collection of Signora Fernanda Giulini, Milan

![]()

8. The keyboard usually slides in and out of the keywell like a drawer. In instruments built north of Naples the keyboard normally needs first to be lifted out vertically and they withdrawn from the keywell.

Photographs showing how the keyboards withdraw from the keywell like a drawer.

Left: the 1677 virginal by Honofrio Guarracino, Naples, Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali, Rome

Right: Single-manual harpsichord by Onofrio Guarracino, 1651, Naples, Collection of Andrea Coen, Rome

![]()

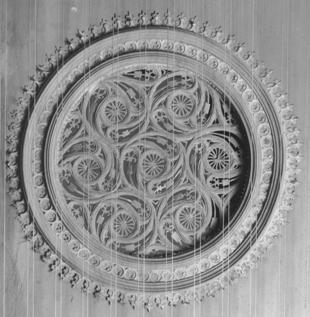

9. The soundboard rosettes are often of a composite nature with a part of the rosette glued to the top surface of the soundboard and a second part glued below the soundboard. These rosettes are in several layers of wood and/or parchment. Often the lower central part is very deep in a kind of 'wedding cake' fashion, and sometimes the top layer is ornamented with one or more rings of moulded wood.

Soundboard rosettes in two Neapolitan harpsichords

Left: Single-manual harpsichord attributed by me to Onofrio Guarracino, c. 1690, Naples, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

Right: Single manual Neapolitan harpsichord, c.1680, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Catalogue Nš M. 1-1933

In some cases such as in the photograph below the keyfronts are also carved in a manner similar to that found on the soundboard rosettes:

Keyfront (arcade) of a Neapolitan harpsichord

Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Cat. Nš 579

![]()

10. Many, but not all, Neapolitan harpsichords have keywell scrolls that are carved blocks often as an extra inserted piece glued to, but not a part of, the spine and cheek.

Examples of carved keywell scrolls

Left: Single-manual anonymous Neapolitan harpsichord, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Cat. Nš 579

Right: Harpsichord attributed by me to Onofrio Guarracino, c. 1690, Naples

Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Catalogue Nš 1933.0543

![]()

11. Often the nameboard is panelled with a central moulded frame carved out of the wood of the nameboard itself and not formed by applying mouldings onto the flat surface of the nameboard.

![]()

12. The nut is in two straight sections with a 'nick' between them roughly at the note middle c (c1). The bass section of the nut is almost parallel to the lines of the tuning pins up to the 'nick' and then the nut heads off towards the register gap.

![]()

13. Very often the sharps, in both the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Neapolitan keyboard instruments, have a decorated top surface. This may consist of several strips of wood, ivory or bone, and sometimes the bits of wood or ivory have been dyed to form a polychrome decoration.

Decorated sharps in the top octave of keys.

Single-manual Harpsichord with a keyboard by Ignazio Mucciardi, c.1770

Padri Redentoristi, Convento di Pagani, Salerno

![]()

14. The keyboard rests on a deep frame glued to the baseboard.

A view into the keywell showing the right-hand third of the deep frame used to support the keyframe and glued to the baseboard. Part of the drawing scribed by the maker onto the baseboard is visible and the line indicating the top note c3 is indicated by the arrow.

Harpsichord attributed by me to Onofrio Guarracino, c. 1660, Naples

Collection of Signora Fernanda Giulini, Milan

![]()

15. Last, but not least, a Neapolitan harpsichord, virginal or spinet must use the Neapolitan unit of measurement in its design and construction. This means that the baseboard dimensions (not including the case sides), the case height, the strings scalings and the lateral string spacing - in fact every aspect of the instrument's design - must be based on the Neapolitan oncia. The most common value of the Neapolitan oncia found in sources on metrology is a unit of length 21.835mm. The analysis of most Neapolitan instruments does indeed give a value for the oncia very close to this. But others use a workshop unit, clearly based on the Neapolitan unit, but that is slightly different from ot. For example, Onofrio Guarracino (1628 - post 1698) used a somewhat smaller unit which, for the dozen or so instruments that I have examined so far, averages about 21.62mm.

![]()

A good example of a Neapolitan harpsichord.

Go

back to the top of the document