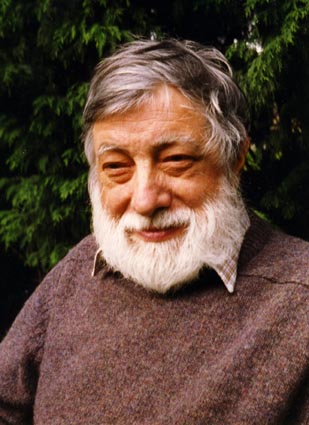

J O H N B A R N E S

A TRIBUTE TO MY TEACHER AND MENTOR

by

Grant O'Brien

Obituary

John Robert Barnes, (b. Windsor, 11 Oct 1928; d. Edinburgh, 9 March 1998).

Scientist, organologist, harpsichord and clavichord builder and restorer. Former Curator of the Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments at the University of Edinburgh.

The passing of John Barnes marks the end of the career of one of the best loved, most highly esteemed, and most knowledgeable figures in the world of early keyboard organology. It is now hard to estimate the influence that he has had in the fields of restoration, keyboard instrument building, and the more academic sides of this field. But his name is both well-known and highly respected by every one of the vast number of people who came under his influence.

John Barnes trained in physics at the University of London and began his career with a firm in England making sound recording tape and recording equipment. At first he worked on wire recording, but was then involved in some of the early work on the deposition of a ferric layer on a plastic film, later to become the basis of the modern tape-recording industry.

During this time he visited the Benton Fletcher Collection of Keyboard Instruments in Hampstead, London, and he also got to know Hugh Gough, one of the first to appreciate the importance of retaining the original features of early keyboard instruments, rather than ‘modernising’ them to conform to the then-prevalent piano customs of the early keyboard revival. In 1962 he began to pursue professionally his interest in early keyboard music and instruments by building and restoring harpsichords and clavichords. Between 1962 and 1968 he restored many of the important keyboard instruments in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the Royal College of Music in London.

He became the first curator of the Russell Collection of Harpsichords and Clavichords at the University of Edinburgh in 1968. As a result of his restoration and examination of many of the instruments of the Italian school in the V&A, the Royal College, and the Russell Collection, he made a number of important discoveries about the stringing and pitch of Italian stringed-keyboard instruments. His approach was methodical and scientific and dominated by the features and measurements presented by the instruments themselves, rather than by any of the contemporary theories and practices. This philosophy dominated his restorations and his approach to the stringing, pitch, regulation, and disposition of harpsichords and clavichords, as well as to their construction. His restorations were always carried out with excellent technical skill, and this was complemented by his methodical scientific approach. He was able to show that careful observation and measurement of all the features of an instrument can lead to the determination of its original compass, as well as to any subsequent alterations in its compass or pitch. As a result of his work and his approach, which treated both original and later, but historical, material in an instrument as inviolate, he also became one of the first to advocate the preservation of instruments without restoring them to playing condition.

His inventive and ingenious restoration techniques had but two aims: to intervene as little as necessary, and to ensure that every procedure that he carried out was reversible to the greatest extent possible. The discoveries he made and the examples he set by his approach have been a model for both his contemporaries and also a whole subsequent generation of keyboard restorers and organologists.

Because of his extensive efforts in the field of restoration, his own keyboard building output has been small, but he has exerted considerable influence through his contact with builders who have visited the Russell Collection, and through his unqualified support of traditional, historical building practices. He affected the production of harpsichord kits along these lines through his association in the mid-1970s with Zuckermann kits, and laterally with the Early Music Shop in Bradford. He was generous in the extreme with his knowledge and expertise. He carried on a voluminous correspondence with harpsichord builders, restorers and players right up until the time of his death, and he and his wife Sheila welcomed scholars and players to their home and to their own private collection of keyboard instruments. The influence that he has exerted in this way has been both enormous and significant.

In the late 1970’s and 1980’s John became increasingly interested in early pianos, and he assembled an important collection of instruments of the English, French and Viennese-German schools. Laterally he also became an advocate of the clavichord, convinced that the study and restoration of this instrument had not kept pace with that of the harpsichord and early piano. To this end he was one of the founding members of the British Clavichord Society, and a staunch supporter of the clavichord conferences and workshops held in Magnano in Northern Italy. A few years ago he bought a Lindholm clavichord which was his pride and joy, and which he played with both verve and considerable skill. His playing betrayed a high admiration for and appreciation of the works for keyboard of J.S. Bach, but he had at his fingertips a vast repertoire of early keyboard music.

He has published widely in all aspects of the organology of the harpsichord, clavichord and early piano. It seems unnecessary to itemise here the many journals and books of international reputation in which his writings have appeared, not the least of which were The New Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, The Galpin Journal, and Early Music. In the early '70’s he taught a course for the Extension Department for the University of Edinburgh, and formed an association with his many students that far exceeded the normal teacher-student relationship. Many of his students went on to take a particular interest in early keyboard instruments and went on to build harpsichord kits or took a renewed interest in playing or building. He was eventually appointed to become a member of the Faculty of Music at the University of Edinburgh, and taught the unit on the early piano for post-graduate students taking the Early Keyboard Organology course.

The influence that John had over me was immense, and I feel certain that my case is typical of many of those with whom John came into contact. I would certainly never have entered the field if it had not been for John’s interest and enthusiasm, and because of his scientific background which was similar in many ways to my own. He was also very generous to me with his time and could always spare a moment to explain some intricate question which might range from anything between an historical building practice to some theoretical aspect of tuning. This did nothing but fire my own interest further and excite my desire to carry out my own research. When I came to his workshop in 1972, one of the first projects we worked on together was a harpsichord loosely (we both thought at the time that it was closely) based on a Ruckers model. My interest in the Ruckers family and their instruments was directly inspired by this activity and his influence led eventually to the publication of my book on Ruckers. But he was also fascinated by the Italian school and my present activity in this field was also inspired by him. During the time that I shared his workshop with him, there were many important instruments undergoing restoration there. The anonymous Italian harpsichord from the Royal College of Music (No 175), the Ham House ‘Ruckers’, the ‘Haydn Clavichord’ by Bohak also from the Royal College, the two Taskin harpsichords and the 1637 Ioannes Ruckers from the Russell Collection, are just a few of the instruments that were in the workshop and that we discussed intently.

John also turned over the restoration of a number of instruments to me from the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome, and often suggested to others when he was asked to carry out restorations that I should do them for him. This then led to further commissions and work, and kept me going in a very financially-lean part of my career. I cannot really express in words how much I owe to him, and how much of a privilege I consider it to have known him and worked with him.

One of the things that I liked most about John was his roguish and slightly impish sense of humour. He was widely read and could often spontaneously produce an apt quote from Ogden Nash on almost any related topic. There was always a spark to his wit and the twinkle of a mischievous six-year old in his 50-odd year old eye. As well as the intensity of the discussions we had there was also a lot of good genuine fun and games and practical jokes. This aspect of John came across to all of those that he met.

John suffered from angina and had a triple heart-bypass in 1985. This restored a new vitality in him, and the very fact that he had to have the operation also strengthened an awareness in him of the necessity of a good diet and a healthy amount of exercise. After his operation he took on a new lease of life and regained much of his earlier vigour. He started to travel abroad again, and to take a renewed interest in instruments and collections outside of Britain. Laterally his asthma, from which he had suffered mildly for a long period, became an increased health problem. He had a mild attack on Sunday March 8, was sent to hospital and died of heart failure complicated by asthma on the following Monday evening. He is survived by his wife Sheila, two children Elizabeth and Peter, and three grandchildren.

- Grant O’Brien

Return to the section on John Barnes