A Franco-Flemish double-manual harpsichord,

![]()

Topics for Discussion

regarding the restoration of the decorative paintwork

Section 1 - Introduction

This document is intended as an introduction to some of the many aspects of the restoration of the paintings and decorations on the instrument. It is reasonably thorough, but is not meant to be exhaustive. It is hoped that the analyses and examinations that are planned will help us to understand the decorative history of this harpsichord and to clarify the periods in which various aspects of the decoration took place. It is hoped, also, that the study of the paintwork will help us to understand the musical alterations to the instrument and to its decorations throughout its history. In the end, of course, the aim of the analyses and the restoration of the instrument is that the instrument will return, not to its state in 1750 or in 1786, but to a state that gives some idea of its splendour and magnificence that it displayed in the historical period.

The immediate motivation for writing ‘Topics’ is that Cinzia Pasquali and Alice Aurand are due next week (April 24-25, 2018) to make the initial assessment of the instrument’s decoration and will perhaps take some samples of the paintwork in order to try to make some clearer decisions about what treatments are necessary and to try to clarify some of the uncertainties about the instruments decorative history: http://www.arcanes.eu/fr/accueil/

The painting of the decorations on the instrument has suffered very badly in the past. This is partly the result of straightforward physical damage, of heavy-handed painting restorers but perhaps mostly as the result of a thick heavy layer of linseed-oil varnish that had badly discoloured and that had cross-linked and attached itself to the underlying paint layers. The removal of this varnish caused a considerable damage and a major loss of paint. During the removal of the varnish layer there were also found to be large patches of red/pink gesso whose presence was much disguised by the layer of dark varnish and indeed to having been painted over to fill in missing lacunae (see the photograph below). The gesso could only be removed mechanically, but this removal seemed to cause less damage than dissolving the layer of varnish. However, in many cases the removal of the bole seemed to cause more damage than it actually did because much of the later retouching was painted on top of the bole and was lost along with it. But there was clearly no paint there before the bole was applied.

The initial photo above gives a fairly good impression of the harpsichord before the thick layer of linseed oil varnish was removed. Much of the painting and decoration underneath this varnish was almost invisible, and could barely be discerned. The varnish was very thick in places and had cross-linked to the underlying paint. In places this had caused serious ‘un-natural’ cracklure, in other places it had simply been subject to creep and had pulled the underlying paint with it as it contracted. The damage caused by the varnish layer across the whole of the exterior of the instrument is the main source of concern and will be the main source of the difficulties encountered in the painting/decoration restoration.

The whole of those surfaces that were varnished with the linseed-oil varnish have been cleaned by local painting restorers whose expertise is in fine art painting restoration. The cleaning process removed a great deal of the original painted surface but this loss was, I think inevitable. Also as mentioned above there seemed to be more loss than actually occurred because the bole had, in many places been painted over. The inside of the lid and the case exterior (cheek, bentside, tail and spine) have ostensibly been restored and re-varnished, but the extensive work that I have now done on Christophe Huet and François Boucher has revealed that there are many problems with the previous restoration work and re-touching work done by the local restorers. This will be discussed in detail below.

This shows a good example of the patches of red bole which was unseen and virtually undetectable underneath the layer of linseed-oil varnish. Unlike the varnish, the red bole was only poorly attached to the surface and could be removed effectively with very little damage to the underlying painted decorations. The paint loss caused by the removal of the linseed oil varnish is clearly evident in this photograph, as it was applied over the whole of the exterior decorated and painted surfaces with the exception of the keywell above the keys.

I have many, many pictures of the painted decorations of all parts of the decorations that I hope will be found to be useful in reconstructing those parts of the decoration that have been lost in the cleaning process.

Section 2 - The lid exterior

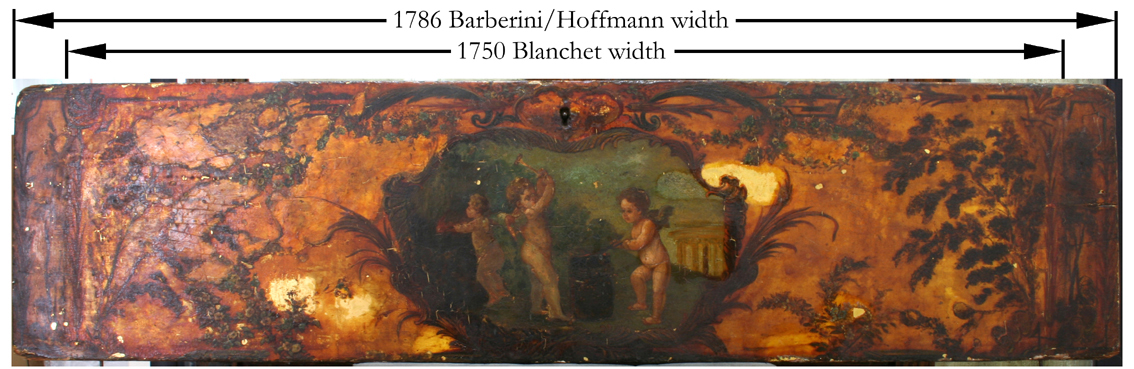

This shows the exterior of the lid as it is now - partially cleaned, but un-retouched and un-varnished.

-

Shows the front lid batten. This batten, like the two shown in 3 (below) is normally not decorated at all in other instruments by Blanchet, and in other instruments of this period by other makers. This particular decoration seems to be carried out using oil as medium and is carefully and finely done. Is there any feature of this that indicates the period and painter who carried it out? It is probably later than 1750 because it includes the decoration on the parts of the batten added in 1786 (see 7 below).

-

There is a great deal of paint loss in this area. Is there any way of working out what was formerly painted here?

-

As in 1 above these battens are normally not painted. Unlike the batten in 1, this batten seems to have been painted using varnish as a medium. Is this part of the decoration by Tomasini’s painter and added in about 1889?

-

It seems likely that there would have been some decoration added to that of 1750 in this area. Can this be re-constructed (or invented to cover over this bare area?). Whatever was there must have been painted in 1786 and a kind of ‘faux Huet’ style in order to match in with the rest.

-

As in 2 above, there is a large area here of loss which we might try to re-construct ????

-

This shows the extent of the added wood and decoration that had to be extended when the treble ravalement took place in 1786. The implications of the 1786 extensions to the three lid battens, to the painting on the inside of the lid, to the jackrail, and to the front lockboard need to be understood clearly and taken into account during the painting restoration and any re-construction.

Unfortunately the local restores did not leave a sample area untouched in order to leave a sample of the varnished and uncleaned surface for future study and analysis. It was hoped that an area under one or more of the hinges could be left uncleaned, but the restorers at the Restoration and Conservation Department at the University of Lincoln, did not correctly follow instructions, and they removed all of the varnish without leaving any of the 'linseed oil varnish in place. Their instructions were quite clear: "Under no circumstances should any varnish found underneath the hinges be removed so that at least some small sample of the linseed-oil varnish remains".

I firmly believe that the figures of Cupid, Flora and Juno on the left of the photograph above are by François Boucher. But the painting of the figure on the right seems to me, for numerous reasons, to have been added after the initial painting of the outside of the lid in 1750. What can be done to analyse this part of the painting to ascertain whether it belongs with the rest of the 1750 decorations and painting?

The figure at the right seems to be that of Marie-Louise O’Murphy, mistress of King Louis XV from about 1753, , and so establishing the author of this part of the painting and its date are crucial to the correct reconstruction of the history of the instrument and its possible commissioning by the French Court.

Section 3 - The lid interior

The inside of the lid has, ostensibly, now been cleaned, retouched and re-varnished.

-

When this work was done the paint at the top of the lid flap at the top left was accidentally removed by the restorers who hadn’t understood the history of the instrument and the sequence of the alterations (ravalements) that the instrument had undergone. Virtually the whole of the ‘rope’ decoration around the lid seems to date to 1786. However, the fact that some, at least, of the paint at the top of the lid must have been dissolved in 1786 may indicate that the ‘rope’ decoration was already there and that it was simply extended to cover the added top part of the lid. The re-painting of this ‘rope’ decoration along the top of the lid flap is uneven and, I think, needs more study. Any putative junction between the 1750 part of the rope decoration and the 1786 decoration must be carefully preserved so as to identify to which period this ‘rope’ decoration belongs.

-

The top of the tree extends here up into the painting of the new wood added to the lid flap in 1786. This and most of the painting of the tree, the sky and the ‘rope’ were removed then and re-painted without reference to the photographs of the lid before it was cleaned. So the top of the tree does not correspond to how it was before the loss of the paint.

-

Unfortunately the local restorers restored the two sections of the lid independently without taking the painting on the other part of the lid into account. This has resulted in numerous discontinuities across the join between the two parts of the lid.

-

The ‘tone’ - the darkness and lack of ‘freshness’ - of the paint on the lid flap is very noticeable and disturbing. Why is this so? What has happened here?? Would it be possible to put the ‘tone’ of the two parts of the inside of the lid back into balance?

-

When the vanish was removed from the inside of the lid the painting at the top - 1 and 2 - was removed. This revealed that there was an enormous ‘drip’ of solvent that had dissolved much of the 1750 painting further down into the centre of the lid flap. Most of the losses of this ‘drip’ were filled in during the restoration by the local restorers, but there is still evidence remaining of the losses as can be seen even in this photograph.

-

There is clear evidence in this area of the original under painting of 1617. This seems to show the tower of a Flemish castle painted underneath the present 1750 painting. There can be no question of uncovering this or of removing the 1750 painting, but perhaps infra-red photography might help us to understand more about the original 1617 Flemish painting.

Section 4 - The Lockboard, cheek, bentside and tail

The figures painted around the surfaces of the outside of the instrument that are normally visible, namely: the lockboard, the cheek, the bentside and the tail are decorated the with a series of paintings, possibly by Boucher, that represent a kind of procession of figures or amorini in a ‘Triumph of Love’ sequence. In art, Cupid often appears in multiples as the amorini, in the later terminology of art history, the equivalent of the Greek erotes (Aphrodite’s retinue). Cupids and amorini are a frequent motif of both Roman art and later Western Art of the classical tradition as they are here. The first of these multiple figures on the lockboard closing the keywell might be seen as the first in the series of ‘The Triumph of Love’, starting with the cupids or amorini forging their arrows. As we move around to the cheek, the Amores are sharpening their arrows on a stone. The detailing of the stone, the pedal used to operate it, the water being spilled onto the stone from a scallop shell are all superbly observed and painted - although heavily and awkwardly overpainted.

Careful observation of the figures in the ‘Triumph of Love’ has shown both that these figures were initially painted by a painter of superlative skill and that they have subsequently been very badly overpainted by some very heavy-handed ‘restorers’. This overpainting has made an assessment of these paintings very difficult, and made the attribution of the original painter of these figures quite impossible.

Part 1 - The lockboard - outside

This photograph shows the outside of the lockboard at the moment the varnish removal was begun. It shows the dark varnish that has so badly damaged the paint and gilding. It also shows the way the lockboard was extended at both ends in 1786 to keep the figures and the lock itself centred on the board.

Here one of amorini figures is heating the arrowheads in a forge at the left. The central amorino wields a blacksmith’s hammer and is beating an arrowhead while the third amorino on the right holds the arrowhead firmly in position on the anvil.

This shows the drastic (and disastrous) losses to the outside of the lockboard.

These three photographs show the central lozenge of the painting on the outside of the lockboard (top left) uncleaned, top right with the varnish removed, but with the red bole which had clearly been painted over to create the top left version and, bottom, the lozenge without the red bole and with the disastrous losses.

Part 2 - The lockboard - inside

The inside, protected, surface of the front lockboard. It has been partially cleaned here, but shows clear evidence of one of the patches of red bole (top left) and of the thick heavy layer of linseed oil varnish.

The inner surface of the front lockboard after cleaning. This shows the differing amounts of new wood added (because of the scarf joint used) and the resulting difference in the reflectivity of the newer gilding.

The lockboard has not, at this stage been re-touched and varnished - this work is still all to be done. There is clearly much loss of paint. The decoration is centred but not symmetrical in the sense that it is not at all balanced in the way one would normally expect roccoco decoration to be. However, the loss and damage on this side of the lockboard is not nearly as extensive as it is on the other, front, side.

The design at the centre of the inside of the lockboard. The paintwork is generally in good condition with only minor losses, although still with considerable work to be done.

Part 3 - The figures in the sequence of ‘The Triumph of Love’:

|

|

|

|

Amour 1 - The amorini sharpen their arrows |

|

Amour 2 - The archer getting a bit of practice. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amour 3 - The badly restored ‘onlookers’. |

|

Amour 4 - Two amorini showing how to do it. |

|

|

|

| Amour 5 - The strong guys |

Amour 6 The charioteer being crowned. The figure standing at the left of the archer really is in need of a bit of re-construction! |

A detail of the archer. Although less re-touched than many of the others, the head seems reasonably intact.

The head of the charioteer - fairly good condition, but still missing many highlights.

A detail of the head of the figure in the Amour 2 scene above but greatly enlarged.

This

figure is perhaps the least ‘restored’ and re-touched and shows the hand of the

brilliant painter who was initially responsible for the whole of this part of

the decoration. The hair and wings

still reveal a large amount of detail with shadow and careful highlights. I feel that this figure gives some idea of the skill and

brilliance of the 1750 painter. On the

other hand, the left hand of this putto can only be described as distorted and

gross as the result of the crude, unskilled overpainting and touching up. Although even in the head of the putto, the

re-touching and over-painting is all too apparent, many important details

remain: the highlights and detailing of

the hair (except in the hair just above his forehead) and wings, and the

painting of the ear with the highlight just at the top. But what is particularly noteworthy is the

painting of the light reflected back off the body of the archer putto onto the

face of this little brunette. This

shows the skill of the painter in its highest and most sophisticated form. Although highlighted with light, the face is

painted with a dark outline to distinguish it from the flesh tones of the body

of the archer putto just behind him. In

my view only a painter at the height of his/her powers could have painted

this.

I

feel that what is needed now is to remove the overpainting and re-touching from

the faces and bodies of the other putti in the ‘Triumph of Love’ sequence to

see if there is further evidence of this skill and technique lying hidden under

the rest of the later over- painting and retouching.

Part 4 - Cupid - the last in the ‘Triumph of Love’ sequence - the figure painted on the tail of the case

Here the left picture is a photograph of the tail after the

varnish and bole were removed but before any re-touching by the local

restorer. The picture on the right is

the present state of the tail after retouching, ‘restoration’ and

re-varnishing.

In classical mythology Cupid is the god of desire, erotic love, attraction and affection. He is often portrayed as Eros, the son of the love goddess Venus and the war god Mars. Although Eros is generally portrayed as a slender winged youth in Classical Greek art during the Hellenistic period, he was increasingly portrayed as a chubby boy. During this time, his iconography acquired the bow and arrow that represent his source of power: a person, or even a deity, who is shot by Cupid's arrow is filled with uncontrollable desire.

In both ancient and later art, Cupid is often shown riding a dolphin. Here he is not riding a dolphin, but it seems highly likely that the figure behind him is meant to be a dolphin and not some kind of an ill-defined monster that has been run through by a baseball bat! The (badly restored) torch in his right hand represents the fire of burning passion. He is also often shown wearing a helmet and carrying a buckler (a small round shield held by hand or worn on the forearm), perhaps in reference to Virgil's Omnia vincit amor or as political satire on wars for love or love as war. The buckler is absent here, but a golden helmet lies at Cupid’s feet.

In art Cupid

often appears, as here, in multiples as the Amores, or amorini. The cupid appearing on the tail of the harpsichord is the final

figure, and the last in the series of ‘The Triumph of Love’, starting with the

cupids or amorini forging the arrows on the front flap closing the

keywell.

Section 5 - The spine side

These photographs both show the condition of the spine side of the instrument. Importantly it should be noted that the spine side of a French harpsichord of the eighteenth century is usually left unpainted and un-decorated. This may be the only eighteenth-century harpsichord with a painted spine (information kindly supplied by Alain Anselm). The fact that this instrument DOES have a painted spine suggests, a) that it was intended to be displayed as the splendid centre-piece of a room and b) that the additional extravagance of this decoration is one of the many features of the instrument that suggests that it was once the property of Louis XV and that its decoration was commissioned for him by Mme de Pompadour.

The many quirky features of the spine decoration are all similar to those of the normal style of Christophe Huet seen elsewhere in the Château de Chantilly, the Château des Champs sur Marne, the National Archives in the centre of Paris, and on the decoration of the 1730 Blanchet double-manual harpsichord in the Château de Thoiry just outside of Paris. There can be no doubt about the authorship of the spine decoration and no doubt that it is an original feature of this harpsichord.

This decoration is generally in good condition, but still needs some work in the light of Huet’s normal style.

Section 6 - Additional images:

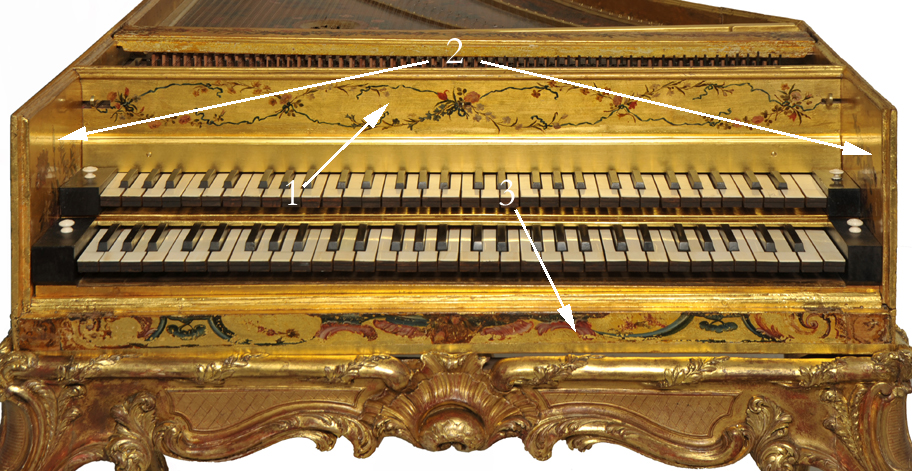

The picture above shows a number of important features:

-

The decoration of the nameboard appears all to date from 1786 and is the only major part of the re-decoration from this period. This and the sides of the keywell (2) appear never to have suffered the varnish treatment that so much of the rest of the instrument has undergone.

-

The decoration of the sides of the keywell is in a style different from almost all of the rest of the instrument. It also appears to have been done using varnish, rather than oil, as a medium. It appears that whoever carried out this decoration was totally unfamiliar with harpsichord decoration as the painting of the flowers does not in any way take into account the eventual presence of the keyboards with their large keyblocks: it seems to have been decorated without the keyboards in place and without taking the eventual presence of the keyblocks into account. Normally this decoration is done so that any of the figures or flowers painted at the sides of the keywell are not covered by the keyboards and keyblocks, but instead fit into the restricted space around them. The most likely possibility is that the sides of the keywell were decorated in about 1889 (or later before it was sold in Sotheby’s in 1927) by a decorator who was unfamiliar with harpsichord decoration. Ideally the pigments and medium of this decoration should be compared with that of the 1786 nameboard decoration, with that of the jackrail and with that of the battens on the lid.

-

The decoration along the lower front edge of the instrument has survived with much less damage than the lockboard that goes above it when the instrument is closed up completely. The decoration surviving here may be a good guide to the original, but now missing, decoration on the outside of the lockboard.

When this, and the decoration on the lockboard are restored, the decorations on the two parts must match in colour, tone and final treatment so that the decoration flows across the join just below the lockboard when it is in its usual position.

Section 7 - The gilding of the visible edges of the baseboard.

During the musical part of the restoration of this harpsichord it was found necessary to remove the South-American plywood baseboard (presumably dating from the ‘restoration’ of the instrument in 1971 by Roberto de Regina in Buenos Aires). Because the baseboard had been renewed and replaced a number of times in the course of the history of the instrument, the lower edges of the case sides have suffered damage in the past. When the new baseboard was given to the instrument in the present restoration by me, these damages were not treated by the gilding restorer but were simply gilded over. They now need to be filled in with gesso, gilded over and the reconstructed paintings around the sides of the case need to extend into the baseboard in a way that is ‘natural’ and in keeping with the rest of the decorations.

We have been very pleased by the work of the gilding restorer who has done all of the work on the gilding of the instrument and the stand. We want her to do a bit more work on the stand, particularly to the feet, but otherwise she has left the stand with a satisfactory patina of age without making it look brand new. Should she be asked to continue this work, or will it be done by Cinzia and Alice?

Although the restoration of the paintwork and decoration is still unfinished, even at this stage this photographs gives a good idea of the splendour and richness of the decoration of ‘Big Goldie’!

See the comparisons with the images photographed under UV light here.

![]()