Franco-Flemish double-manual harpsichord,

![]()

The attributions of various aspects of the 1750 state of the franco-flemish harpsichord

The Franco-Flemish harpsichord has been associated with various important and well-known craftsmen and artists active in 18th-century Paris. Some of these associations are certain and enable positive attributions to be made; others, although less certain are all still at least highly likely:

-

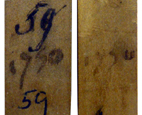

The date of the first grand ravalement, when the compass was F1 to d3, appears on the top jack (jack 58) of two of the three surviving rows of jacks. The writing of the date is clear and unambiguous and is 1750 written on both rows of jacks. The lower guides both still survive and indicate that they are now the result of three successive states in different periods of the instrument's history. These alterations are outlined elsewhere on this site. The alterations show clearly that the state reaching down to F1 and up to d3, is the fourth state of the instrument (see the section on the brief history of the harpsichord). The correspondence of the construction an the numbering of the jacks to the alterations to the lower guides, and with the decoration of the instrument, makes it clear that virtually all of the present decoration must have been carried out in 1750. In the state before 1750 the compass was G1/B1 to d3, squeezed into the original width of the case, but nothing now survives of this state except for the original central part of the lower guides which have been extended at both ends. The 1750 downward extension of the compass from B1 to F1 required an extension of the case width of the instrument on the bass side. The extension to the spine, tail, soundboard, bridges, lid, lid flap, front flap, jackrail and all the internal framing necessary to maintain the structure of the instrument, were all carried out in the 1750 ravalement. But all of the external surfaces that were extended at this time are also all covered over the same decoration added when this extension took place. This therefore dates the decoration of the first grand ravalement to exactly 1750. It needs to be pointed out here that it is sometimes impossible to date a painting or decoration exactly, but in the case of this instrument there can be no doubt about the date of the case paintings, the case decorations and the painting of the inside of the lid (except, obviously for the painting on the treble extensions of 1786 when the treble compass was increased from d3 up to f3).

Click here to see a larger image of the date 1750 on two of the jacks for the note d3.

Figure 1 - The date 1750 on the top d3 jacks of two of the three surviving rows of jacks when it had the compass F1 to d3 with 58 notes.

-

The attribution of the first (1750) ravalement to François Étienne Blanchet is a certainty. That Blanchet carried out the enlargement of the harpsichord in 1750 can be argued from numerous aspects of the alterations carried out to the instrument at this time: the case joins and soundboard joins are carried out with workmanship of outstandingly high quality, the characteristic cutout of the bass end of the 8' bridge (see the diagram below), as well as virtually all of the numbering and construction details of the jacks are all features that point to François Étienne Blanchet as the author of the ravalement.

Figure 2 - The cutout under the end of the 8' bridge of the 1746 Blanchet harpsichord in Versailles (left) and the same feature found on the added piece of bridge on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord (right). The original bridge pins of the Versailles harpsichord and seen on the left seem, unfortunately, to have been replaced with modern pins (the string for the long F# is missing.) Also not original is the gold paint on the bridge in the right-hand photograph, which was probably added by Tomasini in about 1889.

Although not present in the bridges of all of the harpsichords by François Étienne Blanchet, the cutout at the bass end of the 8' bridge is one of the distinguishing features of instruments by Blanchet and is but one of the many features that identify the first grand ravalement of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord as the work of Blanchet, le facteur des clavessins[sic] du roi.

The above features all bear the hallmarks of work by Blanchet. But even more characteristic and individual are the many construction details of the jacks. It is clear that the jacks of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord were made using exactly the same set of jigs that were used to make the jacks of the 1733 Blanchet harpsichord in the Château de Thoiry. When compared with the same features of signed instruments by Blanchet (although there now remains very few Blanchet instruments with original jacks), these same construction features are identical.

Further evidence is provided by a comparison of the hand that carried out the numbering on the jacks starting from ‘1’ at the bass end and continuing to ’58’ at the top end (the compass at this stage was F1 to d3 which has 58 notes). This numbering is clearly by the same hand that wrote the numbers on the jacks and keyboards of the 1733 Blanchet double-manual harpsichord in the Château de Thoiry, and on the keyboards of the 1746 Blanchet double-manual harpsichord in Versailles (the jacks of this harpsichord were lost or destroyed in a modern restoration and so the numbering of the jacks could not be compared). -

That François Étienne Blanchet was 'facteur du clavessins du roi' is matter of known history. He is known to have carried out much of the building and repair of the harpsichords in the palaces and châteaux of the French Court (see paragraph 4 below). This association of Blanchet with the harpsichords used in the French Court is thoroughly documented in the archives. Indeed it indicates that Blanchet's most frequent and important client was the French court to the extent that any surviving harpsichord built or ravalé by Blanchet stands about a 65% chance of having been made for the French Court.

-

The date of the first grand ravalement and the majority of the decoration and ornaments - the outer case painting and the painting and decorations of the inside and outside of the lid - all date to 1750 with certainty (see 1. above) since this painting covers over the ravalement join still visible along the bass edge of the inside and outside of the lid. The landscape on the inside of the lid is definitely NOT older than the rest of the 1750 decoration (part of the painting is on new wood from 1750), although an older (1617?) painting appears to lie underneath the present interior lid painting. This lid painting dates to exactly 1750 with the same certainty and for the same reasons as the dating of all of the rest of the decorative painting. The close correspondence of the alterations of various aspects of the musical states to the alterations to the case and the case decoration indicate clearly and without any doubt that the majority of present decoration all dates to 1750.

It is true, however, that the decoration of the back of the keywell (= the nameboard), the treble bentside extension made in 1786 and, in part, the jackrail decoration all date to 1786 (or later) with certainty since these latter parts HAD to be re-decorated as a result of the new wood added on the treble side of the instrument to increase the treble compass from d3 to f3. The stand which has never been widened to accommodate the wider case probably also dates to 1786. There are, however, some minor additions to the 1750/86 decorations that seem to have been carried out in 1889 when the instrument was owned by Louis Tomasini and used in concerts in Paris for the Exposition Universelle. These decorative alterations are minimal, however, and are clearly apparent on the sides of the keywell to the left and right of the keys, and on the battens on the outside of the lid. The style and execution of these decorations are all clearly distinguishable from the 18th-century paintings and decorations, and do not in any way make the dating or the attribution of the 1750 paintings any less certain. -

The French Court was Blanchet's most important and frequent client. This is known from inventories published by Sybil Marcuse in 1961 (‘The instruments of the king’s library at Versailles’, The Galpin Society Journal, 14 (1961) 34-6) and by Colombe Samoyault-Verlet in 1963 (‘Les clavecins royaux au XVIII siècle’, Recherche sur la musique classique française, 3 (1963) 159) and by William Dowd, ‘The surviving instruments of the Blanchet workshop’, The Historical Harpsichord Volume 1, Howard Schott editor, (Pendragon Press, Stuyvesant, N.Y., 1984) 17-108. It is clear from the Versailles inventories that roughly two-thirds of the harpsichords belonging to The King were the product of Blanchet’s workshop. This must represent a large portion of Blanchet's total output given that he also spent a very large amount of time on repairs, tuning, maintenance, etc of the Royal instruments. Therefore even based only on probabilities, ANY instrument which survives to the present day and is genuinely by Blanchet (or altered by Blanchet), is more likely than not to have been made/altered by him for the French Court. That the ravalement and decoration of this instrument was commissioned by the French Court is therefore highly likely, especially in the light of the other connections it appears to have with the French Court.

-

The ornaments which are painted around the figure paintings are definitely by Christophe Huet and can be positively attributed to him (see the many examples on the main page and in this example). These decorations are in the same style as those in the Chateau de Chantilly, the Chateau Champs sur Marne and in the Cabinet des Singes of 1765 at the Hôtel de Rohan (now the Archives Nationales

) in Paris. Huet was relatively unknown in the 18th-century and he was very little known until the recent Singerie publications which appeared post 2010. Huet was incredibly inventive, and out of his wild imagination he created some of the most amazing ornaments of any French rococo decorator. To create a 'copy' of his work would r equire an intensive study of his style. Having seen most of Huet's public works in and around Paris, I can see nothing that is inconsistent with Huet's style in the decoration of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. The French Court, as represented by the many commissions ordered by Mme de Pompadour in various chateaux in and around Paris, was also one of Huet's most important clients. So Huet is at least a highly likely candidate for the decoration of any instrument commissioned by the French Court. But the presence on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord of many of the unusual and characteristic ornaments, all of which are consistent with Huet's style, confirm the hand of Christophe Huet as the painter of the ornaments on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord.Figure 3 - The decoration of the spine side of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord can all be attributed to Christophe Huet.

A further Huet-Blanchet connection occurs in the Château Thoiry Blanchet harpsichord that was totally decorated by Christophe Huet, mostly with various animated and very anthropomorphic singeries surrounded by Huet’s usual ornaments like those on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. The ornaments on the 1733 Blanchet harpsichord are in an identical style to those surrounding the figure paintings on the lid, bentside and cheek of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. The spine side (see the figure above) was decorated entirely by Huet. There is therefore a Blanchet/Huet connection on two surviving harpsichords: the 1733 Blanchet harpsichord in Thoiry, and this Franco-Flemish harpsichord. Another feature that links this harpsichord to the French Court is the fact that this is the only eighteenth-century French harpsichord in the world with a decorated spine. This makes it clear that the owner was wealthy and that he wanted this object to be the centre of attention in some grand room.

-

François Boucher also had a strong association with the French Court. Mme. de Pompadour was given painting lessons by Boucher, just as she was given harpsichord lessons by Jean-Philippe Rameau. The musical and artistic connection is therefore very strong between both Christophe Huet and Francois Boucher, and with Mme de Pompadour. Mme de Pompadour also commissioned many paintings and portraits by François Boucher.

The figure paintings on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord have all of the usual characteristics of Boucher: the distortions of the face, the shape of the lips, the large, widely-spaced eyes, the high forehead, the awkward painting and modelling of the hands, the excellent modelling of the flesh (there is no trace of the use of pink in the flesh-tones as happens with many imitators), the white doves are almost identical in pose and modelling to those found in numerous Boucher paintings, the painting of the clouds (especially the way Boucher combines the use of white, grey and blue) on which the figures are poised is the same on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord as is seen in numerous of the mythological Boucher paintings (Vulcan at his forge, etc.).

Figure 4 - The heads of Juno and Flora showing all of the usual facial distortions characteristic of François Boucher.

Figure 5 - Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher, Paris, estimated by the Louvre to have been painted in 1750. She is resting her left hand on the keys of a harpsichord that is remarkably similar to the Franco-Flemish harpsichord under discussion here.

The Louvre estimates the date of their Boucher painting of Mme de Pompadour above as 1750, which is exactly the date of the ravalement and decoration of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. I believe that she commissioned the Boucher painting in 1750 which included this instrument because she was proud of her involvement in the ravalement (Blanchet, 1750) and re-decoration of the instrument. This portrait both ties the Franco-Flemish harpsichord to the French Court AND confirms the dating by the Louvre of their painting of Mme de Pompadour with the harpsichord. 1750 is also the time when Mme de Pompadour, because of ill health, could no longer continue to carry out her sexual role as the King’s mistress: she was therefore very keen to remain in the King’s favour, and the commissioning of a number of works by important artists of the time, including the most splendid instrument in the Kingdom, was uppermost in her mind (see below). -

I feel that the figure of the reclining nude (see below) to the right of the figures of Flora and Juno does, in its later altered from, represent Marie-Louise O’Murphy who became Louis XV's mistress in 1753. The examination of the painting of this figure under UV illumination shows that the same pigments and the same technique was used to paint the reclining nude as was used to paint the other figures on the outside of the lid flap and the main lid. As seen from the UV analysis, however, the face of this figure was altered, presumably to make it resemble La belle Morphise.

It is now well known that the numerous representation of the The Brown and The Blonde Odalisque, on which this figure are based, are NOT representations of Marie-Louise O’Murphy. The Odalisque images were done by Boucher before 1750, whereas Marie-Louse O’Murphy did not become Louis XV’s mistress until 1753. So the Boucher Odalisque images all pre-date the arrival of Marie-Louise O'Murphy at the French Court and all have a different face attached to what is, in effect, the same body. My reasoning is that someone (probably NOT Boucher) was asked to alter the image of the face of Marie-Louise on the outside of the lid

Figure 6 - A portion of the outside lid painting showing a reclining nude painted on the outside of the lid after 1750, and probably in 1753 at the time that Marie-Louise O'Murphy became Louis XV's petite maîtresse.I also feel that it is obvious that no-one other than Louis XV (or an official of his Court on the King’s behalf) would have dared to have an image of the King’s mistress painted on their instrument. It therefore follows that the instrument must have belonged to the French Court, and to Louis XV personally. It was the Court who commissioned the alteration of this painting to make it resemble Marie-Louise O’Murphy in 1753. The most likely person to have commissioned this is Mme de Pompadour.

-

There is no other instrument in the world known to me which has an original decoration of the standards and qualities in as richly a decorative style as this Franco-Flemish instrument. Indeed even after a long and thorough search, I have not been able to find another instrument with a decorated spine. From what is known of those instruments owned by the French aristocracy from extant paintings and inventories, they seem usually to have been relatively simply decorated (basically like many of those that survive today) with cases painted in solid colours and with gold-coloured lines or bands drawn around inside the edges of the various case and lid surfaces. So basically they looked very similar to the Blanchet double-manual harpsichord kept in Versailles today (this instrument is not known to have had any connection with Louis XV or his court, and was bought for the Palace of Versailles in 1946). Exceptions to this fashion are the later chinoiserie instruments which are totally different in style to the decoration of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord . Almost all of the other gold vernis-martin instruments are of a much later date than the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. It therefore stands out as an unusual and atypical example of this type of decoration for the period around 1750.

Figure 7 - Probably the most elaborately and finely-decorated French rococo harpsichord in the world.

ANY harpsichord decorated with gold

vernis martin in 18th-century

France was extremely rare. Those few gold vernis martin instruments that have survived from the period around

1750 all have a decorative style that is much stiffer and more formal than the

decoration of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord (see

a typical example of vernis martin decoration here). The decorations of these

instruments are more typical of the formal decorative style of Louis XIV than

the extravagant rococo decoration of this instrument. Indeed, although there

are a few historical instruments with a original gold vernis martin decoration, I know of NO other

harpsichord with an original rococo decoration (I haven’t seen the

1765

François Étienne II Blanchet

double-manual harpsichord in the City of Hamamatsu, Japan). There are, however,

four instruments known to me with a gold vernis-martin rococo decoration, but

all of these are clearly accepted as modern fakes trying to emulate the rococo

style.

There are simply no other instruments

from the period around 1750 with such a lavish, exuberant

decoration. To me this instrument is a simple statement of Mme de Pompadour’s

confidence and her desire to advertise her taste and to broadcast her importance

within Versailles and the French Court, even though she was no longer able to

fulfil her sexual role as the King’s Grande Maîtresse. The sound of

the instrument must have been at least as good in 1750 as it is after the

present restoration. Mme de Pompadour - and presumably those surrounding

the court including François Étienne Blanchet - would have recognised the superb

quality of the sound, and would have wanted the decoration of the instrument to

match the musical qualities of the sound. She

therefore, in my opinion, commissioned Blanchet, Boucher and Huet to fulfil her

project to realise this splendid harpsichord - stunning in its decoration and

brilliant in its sound.

Philippe Macquer in his Dictionnaire portatif des arts et métiers (Yverdon, 1767, Volume 2) p. 7 relates of Blanchet: 'C'est dans cet art d'aggrandir les clavecins de Ruckers que feu Blanchet a réussir incomparablement bien - - - -. Un clavecin de Ruckers ou de Couchet, artistement coupé & enlargé, avec des sauteraux, registres et claviers de Blanchet, devient aujourd'hui un instrument trés précieux.' What was true in 1767 of a Ruckers or Couchet harpsichord is equally true today of an Antwerp instrument even though it is not by Ioannes or Andreas Ruckers, but which has been given an incomparable ravalement by Blanchet!

See also the further section on the attributions of the ravalement of this harpsichord.

- Grant O’Brien, Edinburgh. This page was last revised on 07 July 2022.