Franco-Flemish double-manual harpsichord,

![]()

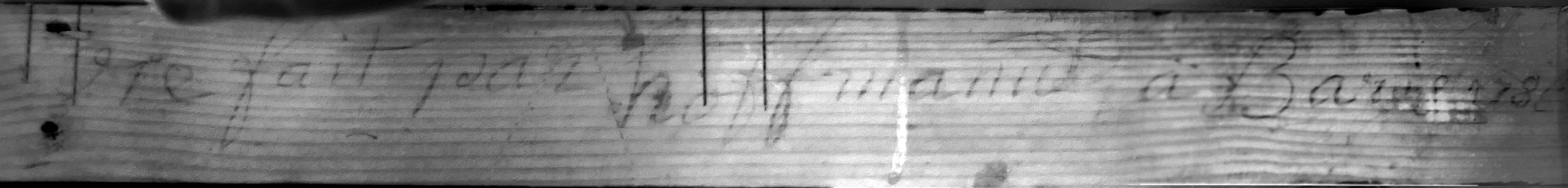

The SIGNATURE OF NICOLAS HOFFMANN ON THE REAR SURFACE OF THE LOWER BELLY RAIL.

The above photograph shows the Hoffmann signature written upside-down on the near surface of the lower belly rail. It is very difficult to read and photograph but says:

"Re fait par N hoffmann à [B]aris 1786"

This photograph was taken with a long exposure, illuminating the rear surface of the lower belly rail with tungsten-filament lamps rich in IR-wavelength light. An IR filter was used on the lens of the camera, and this filter eliminated all light with wavelengths longer than about 400 nm (4,000 Å), and therefore all light except for that in the infra-red part of the spectrum. The photograph therefore represents the light reflected off the lower belly rail only in the IR part of the spectrum. Because the graphite or silver-point used to write the signature does not reflect light in the IR part of the spectrum, the signature then appears as black and clearly visible in the photograph.

The signature occupies the whole of the length of the lower belly rail, and therefore belongs to or post-dates the treble widening of the compass. This signature therefore ties the second ravalement of the harpsichord to the workshop of Nicolas Hoffmann, working in Paris at the end of the eighteenth century. Unfortunately it is not clear which work was carried out by Nicolas Hoffmann, and which was carried out by Jacques Barberini whose name was found on a calling card attached to the post-ravalement baseboard. But unfortunately the post ravalement baseboard was replaced by Roberto de Regina (still alive in 2021) with a baseboard of tropical plywood in his 'restoration' of 1971. This has therefore destroyed evidence of the intervention of Barberini. De Regina also destroyed many of the other features of the instrument which he believed were 'out of period' for an instrument made by a maker belonging to the tradition of the Ruckers family. This simplistic view led to his destruction of the unique genouillère, greatly to the detriment of our knowledge of the late-18th-century history of the instrument, of harpsichord building and of musical history. There now seems to be no way of recuperating this lost information, and this clearly points out the lack of understanding of this minor figure in the restoration history of the harpsichord.

![]()

I would like to express my thanks to Riccardo Angeloni for his help and co-operation in securing this difficult photograph.

![]()

Return to the main page of this section